Two years ago, my heart started breaking. It was a long and painful process. Many things happened before that night, many things happened after, and many things keep happening. I’ve been breaking for decades now.

Most of all, on that evening, I realized I hadn’t ever achieved my–then–lifelong goal of fitting in. I still don’t fit in. The moment when I fit in will never come. Goal trashed–new goals sought!

But it doesn’t matter, my therapist said. It really, truly, doesn’t matter at all.

And how about feeling rejected all the damned time? That was a thing I realized on that night two years ago, too. I always was and would always be rejected. Don’t ask me why, because I wouldn’t be able to tell you. I’m obviously biased in that I have no objective sense of the world–if such a thing even exists.

The question I’m increasingly faced with these days is, what now?

So you tried to fit in, for decades. It didn’t work. Anything and everything you touched crumbled to bits, too. You might have some as yet undiagnosed disorder–friends keep insisting on ADHD, commonly mistaken for or coexistent with BPD, depression, ASD, anxiety, and, my all-time favorite-slash-what describes-me-perfectly, Rejection Sensitive Dysphoria. My one and only point of success is: I have a husband and a family. I’m rockin’ it, eighteenth-century-style.

Okay, okay. So, there’s the rejection part, and there’s the self-worth part. Oh boy, the self-worth part is below basement level right now. I can honestly find no purpose in my existence. And, newsflash, there’s not much joy either if you don’t have a little bit of money to enjoy life with. Yes, yes, money doesn’t bring happiness, but being in a state of debilitating insecurity about present and future isn’t fun. Money does bring some measure of happiness when it takes away a mountain of stress–when it makes you feel a little safe in your present and the thought of the future doesn’t cause you overwhelming anxiety. But I’m a dumpster fire in the jobs department. Absolutely useless.

So, no point in existing. And lying down and dying isn’t an option either. What the fuck do I do?

In a sense, there’s been progress. Let’s start with the Rejection Sensitivity part. That friend from my town who’d been a constant, if somewhat rare, presence for years, and who’s been ghosting me for over a year now? Something like that would have absolutely broken me two years ago. But today? I cried about it once. This is, after all, how life is. She can do whatever she wants; she might have her own problems to deal with. Maybe it doesn’t reflect on me. Or I might be too much for her–heaven knows I’m a whole lot for people to handle. So, I only felt rejected for a little while. Didn’t fall apart. Yay, me.

That guy I sacrificed nearly two years of mental health for? In essence (but not technically!) I was the one who broke that off by, I don’t know, being scary, I guess. I wasn’t willing to give a person the lukewarm, talk-to-you-quarterly friendship he seemed to want, after us being thick as thieves for half a year. Friendships, for me, are not a matter of simple spatial proximity.

People rejecting me and leaving me in many imaginative ways happens all the time. But, these days, I’m learning to protect my time and energy, too. My friends (there are a precious and special handful of those, happily) keep telling me I’m often taken advantage of, sometimes by manipulators, conscious and unconscious, sometimes by self-centered bullies who don’t care about my well-being. There is some truth to this, which I’m reluctantly beginning to accept. It’s a process. I’m not there yet, but doing better is all you can do as a human.

As for self-worth? I don’t think we should discuss this right now. It’s abysmal. I know what I can do, what my talents are. What’s more, I know what I can’t do, what I haven’t achieved, and how every single person on the planet is doing better than me in advertising their value and getting something for it.

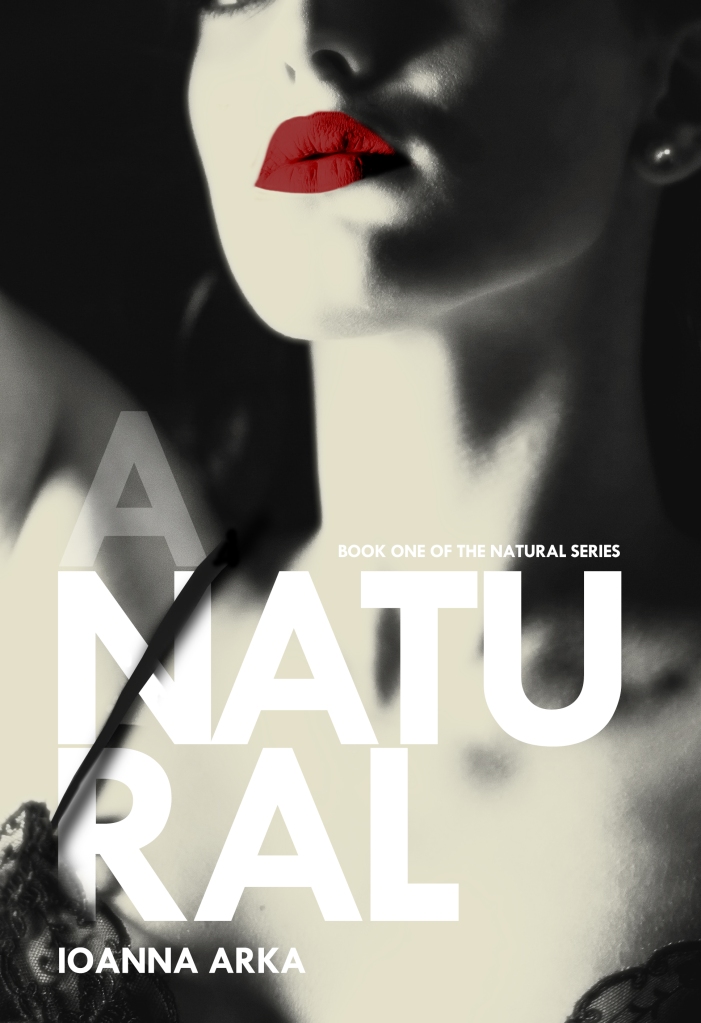

The question, what now, hasn’t been answered yet. Honestly, I have no idea what now. I know I want to publish books, but good as my books are, I’m an idiot in advertising and selling them. And it doesn’t help that many of the people who tell me we’re in the same boat, and they are idiots in advertising too, sell dozens to hundreds of their books. How worthless are you if people who feel worthless are way above you?

Okay, time to wrap up this anniversary post. Two years ago, someone started breaking my heart. Two years on, that job has been taken over by the most efficient heart-breaker–myself. Maybe I can convince me to give me a break.